IMPORTANT NOTES

Information added or updated since this page went live on February 28, 2024, is in GREEN TEXT below.

Information still to be determined (if any) is in RED TEXT below.

Dates and times that are subject to change at NASA’s discretion are in PURPLE TEXT below.

Last update of this page: August 27, 2024, 12:00 pm ET

Quick Links to Sections Below

1. Introduction to the FME Mini-Laboratory

2. Operating the FME Mini-Laboratory

3. Ways to Think About Using the Different Types of FMEs—Some Examples

4. Fluids Mixing Enclosure (FME) Kits – You Get the Real Flight Hardware and Load It for Flight to ISS

5. Mixing the Experiment Samples in the FME Once in Orbit: Available Crew Interaction Days and Allowed Crew Interactions

6. Critical Experimental Design Constraints

– 6.1 FME Dimensions, and Volumes for Fluids and Solids

– 6.2 Experiment Samples—Restrictions on the Fluids and Solids That You Can Use in Your Experiment

– 6.3 Constraints Due to the Flight Timeline for SSEP Mission 19 to ISS

– 6.4 Temperature (Thermal) Control

– 6.5 Sterilization

– 6.6 Lack of Light

– 6.7 Other Important FME Constraints

This page provides information regarding the mini-laboratory used for experiments on SSEP Mission 19 to ISS — the Nanoracks Fluids Mixing Enclosure (FME) Mark II Mini-Laboratory, which Nanoracks has also referred to as a “Mixture Tube” or “MixStik”. To minimize ambiguity, SSEP webpages and documents will refer to the device as an “FME Mini-lab” or “FME“.

On this page you will find all the specifications for the FME Mini-lab, a description of its straightforward operation, and all the constraints on your experimental design, including constraints due to the time it takes from shipping of your experiment to Houston, to arrival and operation on ISS, to return to Earth, and to return shipping to your community.

To the Student Researcher: There are countless microgravity experiments that can be done in the FME Mini-lab. But before designing an experiment, your team needs to fully understand what a microgravity experiments is. It is an experiment conducted in a ‘weightless’ environment where it appears as if gravity does not exist – think astronauts floating in the International Space Station (ISS). You also need to understand why one would want to conduct such an experiment. This is fully addressed on the Designing the Flight Experiment page, and all the content on that page was covered for your teachers during a training program before the start of Mission 19.

Here is the core conclusion – the objective of a microgravity experiment is to assess the role of gravity on something you want to study, which could be something in the realm of biology, chemistry, or the physical sciences. What to study is up to you. To assess the role of gravity, you need to change gravity and see what happens to what you are studying.

Basic Microgravity Experiment Design: Your Flight Experiment will be transported to ISS where it will operate in a weightless environment as if gravity is turned off. But to determine the role of gravity on what you are studying, one needs to compare the flight experiment on its return to Earth to an identical experiment conducted at the same time on Earth – in the presence of gravity. This is called your Control Experiment.

The Big Misconception: you need to change gravity … but you cannot change gravity, which is a force exerted by all of planet Earth on what you are studying. By conducting your experiment on ISS, you are actually tricking the experiment by taking it to an environment where gravity appears to be absent. The astronauts are not ‘weightless’ (floating around) because there is no gravity in space. The force of gravity on them (their weight) is nearly identical to what it is here on the surface of the Earth. They appear to be weightless because the ISS is in a state of continuous ‘free fall’, and whenever you put something in free fall it will experience weightlessness.

If you do not have a clear understanding of what is described above, you do not have the basic information needed to start designing your experiment, and to understand this Mini-lab Operations page. You first need to carefully review the Designing the Flight Experiment page with your teacher, and your teacher is likely doing this with your entire class.

1. Introduction to the FME Mini-Laboratory

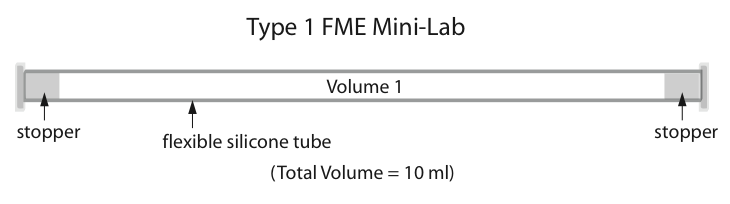

Figure 1: A Type 1 FME Mini-lab containing 1 volume for fluids and solids. CLICK ON IMAGE ABOVE FOR ZOOM

The FME Mini-lab is a very simple mini-laboratory designed to carry small samples of fluids and solids—the Experiment Samples—and provides for the samples to be mixed at an appropriate time in orbit. This allows you to explore the effects of microgravity on a physical, chemical, or biological system contained in the Mini-lab.

The FME Mini-lab consists of a single silicone tube that can contain one, two, or three separate volumes of fluids and/or solids. The tube is divided into sub-volumes using up to two tube clamps. You can think of the FME Mini-lab as one, two, or three small test tubes that can be mixed in orbit.

Each tube is 6.7 inches long (170 mm), with an outer diameter of 0.5 inches (13 mm) and an inner diameter of 3/8-inches (9.5 mm).

Each flight experiment for SSEP Mission 19 to ISS must be designed for operation in an FME Mini-lab. The SSEP payload to the International Space Station (ISS) will contain one FME Mini-lab for each flight experiment. The FMEs will be placed in a Payload Box which can contain up to 8 FMEs. SSEP flight experiments will share the Payload Box with experiments from professional researchers in academia, industry, and government. Nanoracks has the ability to fly multiple Payload Boxes to accommodate a payload of more than 8 FMEs. Once in orbit, the Payload Box is placed in a rack on Kibo—the Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) on ISS.

2. Operating the FME Mini-Laboratory

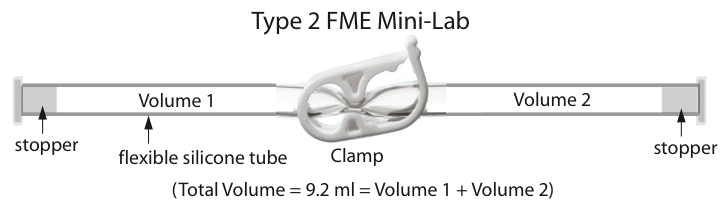

Figure 2: A Type 2 FME Mini-lab containing 2 volumes for fluids and solids. CLICK ON IMAGE ABOVE FOR ZOOM

The FME Mini-laboratory is a single silicone tube that can be divided into sub-volumes via clamps. At a prescribed time, an astronaut can open a clamp and shake the FME Mini-lab for a specified amount of time and intensity allowing the contents of the adjacent volumes to mix. “Open Clamp” and “Shake” are examples of allowed “Crew Interaction Requests”, which a student team can request of the astronauts.

There are three types of FMEs depending on how many different ‘test tubes’ your experiment will need—

Type 1 FME: contains only 1 experiment sample and no clamps. An experiment using a Type 1 FME by definition requires no mixing. Figure 1 provides a graphic of a Type 1 FME. Download Figure 1 as a pdf

Type 2 FME: contains 2 experiment samples, with the samples divided by 1 clamp. The samples do not need to be equal in volume. Figure 2 provides a graphic of a Type 2 FME. Download Figure 2 as a pdf

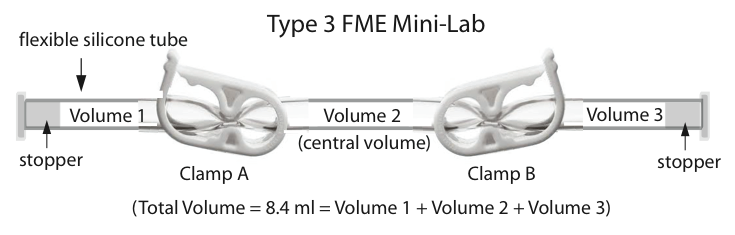

Type 3 FME: contains 3 experiment samples, with the samples divided by 2 clamps. The samples do not need to be equal in volume. Figure 3 provides a graphic of a Type 3 FME. Download Figure 3 as a pdf

Air Voids: A volume containing a fluid does not need to be completely filled. Air voids are fine.

3. Ways to Think About Using the Different Types of FMEs—Some Examples

Provided below are ways to think about using the different type FME Mini-labs for microgravity experiments. But first some important considerations: i) your flight experiment will be in Earth gravity from the time you load it until it gets to orbit, where it will experience microgravity (weightlessness), and ii) your flight experiment will experience Earth gravity from the time it returns to Earth until it is received by your student team for comparison to the control experiment.

This should prompt you to assess if your flight experiment should only be operating in microgravity aboard ISS. If needed, the different types of FME Mini-lab give you the ability to activate your flight experiment once it gets to ISS, and terminate (deactivate) it on ISS before returning to Earth.

A Type 1 FME: provides for an experiment that is ‘pre-loaded’ before launch, and requires no mixing of sample materials once in orbit. It may be that just exposure to microgravity for 4-6 weeks on ISS is enough to conduct the experiment.

Example: an SSEP flight experiment was designed to test if synthetic blood has the same long shelf life in microgravity as here on Earth, which is an important question for addressing medical emergencies in space that require a transfusion. On long duration space flights, there will be no means to carry whole blood given its short shelf life. The experiment required a Type 1 FME filled with synthetic blood sitting on ISS for many weeks, and on its return to Earth assessing if it degraded as compared to synthetic blood on Earth from the same manufacturing lot. The synthetic blood on ISS was in a microgravity environment for 4-6 weeks while the ground control experiment was in Earth gravity for that entire time.

A Type 2 FME: is for an experiment that requires two separate samples to be brought together. A good example is an experiment that requires a single mix to activate the experiment but does not need to be terminated, or cannot be terminated.

A consideration – it will take a few days from the time the flight experiment returns to Earth until it is received by the student team for comparison to the control experiment. If the flight experiment is not terminated on ISS, it will be operating in Earth gravity for just a few days, assuming comparison takes place immediately on its return to the team. If the time the flight experiment is operating in gravity is small relative to the experiment’s duration in microgravity aboard ISS, the experiment can be viable and a Type 2 FME is effective. But if the student team is not ready for comparison when the flight experiment returns, it will continue operating in gravity, and by the time the comparison is finally made the experiment results may be inconclusive or the experiment will have failed.

Another consideration – timing can be crucial. If using a Type 2 FME for a biological experiment, the experiment can be activated on arrival at ISS. But without the ability to terminate the experiment the biological can die and decay over the long 4-6 week duration on ISS. One approach is to start the experiment closer to departure from ISS. Another approach might be to use a Type 3 FME (see below) to introduce a biological fixative to kill and preserve the biology before return to Earth.

Example: an experiment to assess if gravity plays a role in the oxidation of iron. Once on ISS, a Type 2 FME is used to introduce salt water to iron to initiate oxidation. It is an experiment that cannot be terminated. Oxidation proceeds for 4-6 weeks in microgravity. On return to Earth, the flight experiment is compared to the control experiment to assess differences in oxidation.

A Type 3 FME: is for an experiment that requires three separate samples to be brought together. A good example is an experiment that requires a first mix to activate the experiment, and a second mix to shut down the experiment. This is critical if you only want the flight experiment to operate in microgravity, where activation occurs once the experiment arrives on ISS, and deactivation occurs before return to Earth.

A Type 3 FME is particularly well suited to biological experiments where a dormant form of the biological is activated on ISS by introducing a growth medium with the first mix. The experiment is terminated before return to Earth with a second mix by introducing a biological fixative such as alcohol, formaldehyde, or glutaraldehyde which kills and preserves the biological. For more information on experiment termination, read the Using Biologicals in SSEP Experiments: Dormant Forms, Fixatives and Growth Inhibitors document downloadable at the Document Library.

Example: astronauts on long duration space missions will need to grow their own food. But biology behaves differently in microgravity. A middle school team wanted to see if seed germination rates are different in microgravity for food crops. If rates are lower in microgravity, it could adversely impact food production. Dried lettuce seeds were placed in the first volume.

Once on ISS, distilled water was introduced to hydrate the dry seeds. Cotton around the seeds was used to wick the water to the seeds. After 2 weeks, alcohol was introduced to kill and preserve the seedlings. If the experiment was not terminated, the seedlings could die and decay before returning to Earth. On Earth the student team was conducting the same experiment as a control at the same time. When the flight experiment returned to Earth the team could determine the percentage of seeds that germinated in space and compare it to that determined for the control. Through visual inspection they could assess if there were obvious differences in, e.g., root ball shape. Using high resolution microscopy,, they could assess if there were differences at the cellular level.

Example: a high school team wanted to assess if a microbiological was more virulent in a microgravity environment, which could pose a health risk to the astronauts. On ISS, a lyophilized (freeze dried) biological was hydrated using a luria broth growth medium with a first mix. 2 days later, a second mix introduced glutaraldehyde to kill and preserve the colony. The student team assessed that termination after 2 days was important since colonies can grow rapidly, overwhelm the FME, and die. Once the flight experiment returned to Earth, the team was working with local university researchers that had laboratory analysis capability beyond the resources of the school district. The researchers and students did the analysis together, which allowed them to assess colony size differences between flight experiment and control experiment – a measure of virulence. High resolution microscopy allowed them to see if there were morphological (appearance) difference as the cellular level.

Note on the importance of a Control Experiment: a Control Experiment (for SSEP, sometimes referred to a Ground Truth Experiment), is one that is identical to the Flight Experiment in orbit, except it is conducted on the ground by the student team at the same time the experiment is conducted in orbit by the astronauts. To determine the role of gravity on what is being studied, one needs to compare the flight experiment on its return to Earth to the control experiment. A control experiment is therefore always a vital element of microgravity experiment design. In addition, an experiment team should consider conducting multiple control experiments, since this is straightforward to do, and provides more data that can be used to define an average behavior on the ground.

To gain an understanding of the kinds of experiments possible in microgravity, first read, and then

i) look around your world

ii) do an online search of microgravity experiments conducted in space

iii) read the Microgravity Science Background and Microgravity Experiment Case Studies documents available for download at the Document Library.

iv ) red the Experiment Samples document available for download at the Document Library.

v) You can also read summaries of all SSEP experiments selected for flight to date. There is also a page dedicated to Undergraduate experiments.

4. Fluids Mixing Enclosure (FME) Kits – You Get the Real Flight Hardware and Load It for Flight to ISS

As part of the Baseline Program Cost, each participating community will receive:

i) a package of two Fluids Mixing Enclosure (FME) Demo Kits once the community begins Mission 19 activities with their students. The demo FMEs are NOT flight certified and are only to be used by the community to demonstrate to students the size and operation of an FME. (If a community needs more demo FMEs, we can provide vendor information on where you can purchase the generic components.)

ii) a package of five flight certified Fluids Mixing Enclosure (FME) Kits once the community’s flight experiment is selected. Each Kit provides all the parts for the assembly and loading of a flight certified Type 1, Type 2, or Type 3 FME. (If a community needs more than 5 FME Kits, they can be purchase a package of five Kits for an additional cost, depending on availability.)

Figure 3: A Type 3 FME Mini-lab containing 3 volumes for fluids and solids. CLICK ON IMAGE ABOVE FOR ZOOM

Each flight certified FME Kit provides the ACTUAL flight hardware. Each experiment selected for flight will be conducted in an FME that the student team assembles from one of their 5 Kits, loads, seals, and ships or hand-carries to Nanoracks in Houston for flight on the ISS. When Nanoracks receives your FME, they will heat seal two polyethylene bags around it to serve as a second and third level of containment (see Section 6.2 below), add an additional zip tie and sealant to each end, load it in the Payload Box, and deliver the entire payload to NASA for integration into the launch vehicle.

NOTE: the package of five flight certified FME kits MUST be put aside for use by only the selected flight experiment team. 2 FME kits can be used by the flight team for testing, refining and optimizing their flight experiment. 1 FME kit is to be used for the flight experiment. Up to 2 FME kits are for the student team to conduct their ground control experiments at the same time the flight experiment is conducted by the astronauts (see Section 3).

On return to Earth, the sealed FME will be shipped back to you, or provided to your team’s representative in Houston. Once received, the student team conducts their own harvesting of the samples from the flight FME and ground control FMEs, and analysis of the samples.

This approach allows students to get broad experience in all aspects of their experiment design and operation, and there is no third-party handling of the experiment samples before they are sealed in the FME destined for space.

Important notes on testing and refinement of proposed experiments: All experiments that are being proposed as part of the community-wide design competition should be tested to the extent possible using standard laboratory test tubes and mixing protocols, in advance of writing any proposal, in order to assess if the experiment is viable. The data from these tests should in fact be incorporated into the proposal. Once the flight experiment for the community is selected, the student flight team needs to test, refine, and optimize the experiment using an actual FME before the final lock-in of the flight configuration of the experiment. To optimize their experiment, the student team typically has the following time available:

i) 5-8 weeks from the time of selection of their experiment for flight until they must fully identify their Experiment Samples (and the corresponding maximum volumes and concentrations to be used) for submission to NASA Toxicology for Flight Safety Review, and

ii) the period from submission to NASA Toxicology through 2 months before launch, though during this period no Experiment Samples can be added, and the volumes and concentrations of the Experiment Samples cannot be increased, only decreased (see the Mission 19 to ISS Critical Timeline for more information).

Important note on mini-lab assembly and loading: Nanoracks has created videos with detailed instructions for assembling, loading, and sealing the FME. The videos are found in the Document Library. In addition, Nanoracks will be available live via the Loading & Shipping Videoconference during the actual loading of experiment samples into the flight mini-lab by the flight experiment team.

5. Mixing the Experiment Samples in the FME Once in Orbit: Available Crew Interaction Days and Allowed Crew Interactions

Specific astronauts on ISS will be assigned to oversee operation of the SSEP payload of experiments, and will receive training by Nanoracks on FME operation. Note, however, that to ensure SSEP operations fit within the overall schedule of crew activities, and to ensure astronaut training covers all possible FME interactions, Nanoracks in concert with NASA has defined–

Five Allowed Crew Interaction Days: there are only five specific days while the SSEP payload is aboard the space station when astronauts will be able to interact with the FMEs. These are designated the “Crew Interaction Days”, and are the only days that can be requested by student teams for crew interactions.

Allowed Crew Interactions: NASA has defined a list of likely the only specific crew interactions allowed with the FMEs. These are designated the “Allowed Crew Interactions”.

Important note: All student teams designing microgravity experiments must ensure that their experiment proposal only requests interactions on the allowed Crew Interaction Days, and only requests Allowed Crew Interactions. Any proposal submitted by a student team that does not adhere to these requirements should be rejected by the community and not forwarded to the community’s Step 1 Proposal Review Board.

5.1 Allowed Crew Interaction Days for Mission 19 to ISS

Student teams can only choose Crew Interaction Days from the Table below for the assigned astronaut to manipulate their FME – days which best fit their experiment design. For the days listed below, A=0 is the Day of Arrival, when the SSEP experiments payload is brought from the ferry vehicle through the hatch on ISS. U=0 is the Day of Undock, when the ferry vehicle with the SSEP experiments payload undocks from ISS for return to Earth.

| Crew Interaction Day | Description | Day |

| 1 | on arrival at ISS | A=0 |

| 2 | during first week | A+2 |

| 3 | 2 weeks prior to undock | U-14 |

| 4 | in week prior to undock | U-5 |

| 5 | in week prior to undock | U-2 |

Important note on adjustments to scheduled crew interaction days: NASA reserves the right to adjust crew interaction days in the event the crew has other assignments that must be addressed at that time, and/or if the interaction day falls on the weekend it may be rescheduled to a weekday.

Important note on the duration of your experiment: the significant length of time from handover of your FME to Nanoracks in Houston through its arrival on ISS implies that most experiments will need to be in a dormant (inactive) state until arrival on ISS (see Section 6.3 below for constraints imposed by the timeline). If your experiment is inactive until initiated with a mix, then your experiment can be initiated (activated) on any Crew Interaction Day listed above with an astronaut unlatching a clamp. In addition, you might design an experiment that can also be terminated with a second mix, which is possible using a Type 3 FME. You then have the latitude to define how long your experiment should proceed in microgravity before de-orbiting and returning to Earth. But only the Crew Interaction Days in the Table above are allowed. For example, if you only want your experiment to run for two days on ISS, you can choose Crew Interaction Days that are two days apart (A=0 and A+2 above). If you want your experiment to run roughly two weeks, choose Crew Interaction Days that give you a roughly two-week run time for your experiment (U-14 and U-2 above). Also note that the crew interactions you define for your experiment are independent of any other FME experiment being performed.

For the five Crew Interaction Days in the Table above, an experiment can run for: 2 days, 3 days, 9 days, and 12 days. Also note that the time from Arrival to Departure is nominally 4 to 6 weeks. Through choice of Crew Interaction Days, an experiment can also run for the entire time it is aboard ISS (from A=0 to U-2), as well as approximately 1 to 2 weeks less than the entire time (from A=0 to U-14). It is also important to take into account the temperature you can expect on ISS, which may critically impact your choice of Crew Interaction Days, see Section 6.4 below.

5.2 Allowed Crew Interactions for Mission 19 to ISS

Each FME is self-contained, allowing each student flight experiment team to select appropriate Crew Interaction Days when mixing is to take place for their experiment. In the case of a Type 3 FME, mixing would require at least two crew interactions. To mix samples in the FME, the astronaut is instructed to “Open” the appropriate clamp, and should also be instructed to “Shake” the tube at a specified intensity. An example of a crew interaction request to mix samples is “Open Clamp A, Shake gently for 30 seconds”. Allowed crew interactions also include a request to “Wait” a period of time between two interactions, and to “Close” (which means re-clamp a particular clamp).

The only currently Allowed Crew Interactions are listed in the Table below, along with appropriate modifiers that can be used.

| Allowed Crew Interactions That Can Be Requested | Allowed Modifiers |

| “Open Clamp” | none |

| “Close Clamp” | none |

| “Shake” | Requests to Shake must include one of each of the following types of modifiers: 1. Intensity of shaking: “gently”, “moderately”, “vigorously” 2. Duration of shaking (in units of 15 seconds not to exceed 120 seconds): “15 seconds”, “30 seconds”, “45 seconds”, “60 seconds”, “75 seconds” “90 seconds”, “105 seconds”, 120 seconds” |

| “Wait” | Requests to Wait must include the following modifier: Duration of wait (in units of 15 seconds not to exceed 120 seconds): “15 seconds”, “30 seconds”, “45 seconds”, “60 seconds”, “75 seconds” “90 seconds”, “105 seconds”, 120 seconds” And may include the following modifier: “expose to ambient light” |

Important note on the total time that can be requested per day: the maximum total time per FME on any one Crew Interaction Day is 120 seconds.

Important note on the order of unlatching the two clamps for a Type 3 FME: to guard against human error in opening clamps for the Type 3 FME, Clamp A (located between Volumes 1 and 2) will be the first clamp opened by the astronaut, and will be color-coded as a GREEN clamp for the astronaut.

There are two possible configurations for opening Clamp B (located between Volumes 2 and 3):

i) Clamp B is opened at the same time as Clamp A. In this case Clamp B will also be color-coded as a GREEN clamp.

ii) Clamp B is opened on some later Crew Interaction Day. In this case, Clamp B will be color-coded as a BLUE clamp.

Important note on other possible crew interactions and interactions that are not allowed: If a student team wants Nanoracks to consider allowing an interaction other than what is provided in the Table above, please alert NCESSE as soon as possible. The likelihood of any other interactions is very low, but NCESSE is willing to assess the request with Nanoracks and NASA on a student team’s behalf. However, there can be no request for the astronaut to: observe what is happening in the FME; take notes; photograph the FME; or videotape the FME. There is no means to request that astronauts photograph, and by extension videotape a mini-lab. That would require an astronaut to get an available camera, set up the mini-lab for photography – not easy in a microgravity environment, read specific instructions as to what they are to photograph, take the photos, assess if the photos captured the needed information, re-shoot if needed, download images to a computer, telemeter the images to the ground, Marshall Spaceflight Center relaying the data to Johnson Space Center (JSC), JSC relaying the data to Nanoracks, Nanoracks to NCESSE, and then to your team. And if the experiment is designed to critically depend on a photo, but the astronaut does not take the photo showing what is needed, or a camera is not available, then the experiment has failed. The level of activity in terms of what one thinks of as simply taking a photo aboard ISS is huge. Asking for a photograph or a video is in reality asking for a huge effort on station, and can put the astronaut on the hook for getting a photo deemed successful or the experiment fails. So photos and videos are not a possibility. There is no means to ask the astronaut to observe the mini-lab and record notes for the same reasons: i) the tube is translucent making observation difficult, ii) it is not appropriate for an experiment to be designed where success critically depends on observations and notes taken by an astronaut, and iii) the time that would be needed to carry out observations and record notes, across the entire payload of mini-labs, and then getting those notes back to the ground and to the student team, goes far beyond the crew time NASA allots to the SSEP payload of experiments.

Why requests for the astronaut to photograph, videotape, or observe and take notes are not allowed

The FME tube is translucent due to a “parylene” coating to prevent fluid diffusion through the walls of the silicone tube. But regardless of the limited visibility through the tube wall, there is no means to photograph or videotape the samples. Astronaut time is fully scheduled by a crew scheduling team at Marshall Spaceflight Center, and as you can imagine, astronauts are exceedingly busy on station. The SSEP payload is given a block of time on specifically the 5 scheduled Crew Interaction Days. The fact that NASA has dedicated these blocks of time to SSEP speaks to the commitment to the program, but there is a limit on how much crew time we can secure.

6. Critical Experimental Design Constraints

Just like a professional researcher using a pre-existing laboratory or lab apparatus, you need to design your experiment to the constraints imposed by the equipment you are using and the environment in which it is to operate. Listed below are the critical design constraints you need to consider regarding: 1) the Experiment Samples (fluids and solids) that can be used; 2) the design of the FME and its operation on ISS; and 3) how long it will take: a) from receipt of your FME by Nanoracks in Houston to the time it arrives at ISS, and b) from your FME’s departure from ISS until it is received by you.

6.1 FME Dimensions, and Volumes for Fluids and Solids

The FME is a mini-laboratory, which means the volumes for experimental samples are small. So be sure you design an experiment with the specifications below in mind.

Interesting Facts: flying crew and payload to Low Earth Orbit is exceedingly expensive, e.g., NASA currently pays SpaceX $55,000,000 to fly a single astronaut to ISS (that is about $320,000 per pound for a 170 lb astronaut). The volume and mass of payloads must therefore be kept low to keep costs manageable. That’s why the FME as a professional microgravity mini-laboratory is small. But ‘small’ is relative – the volumes listed below are 50 times larger than those for the professional microgravity mini-labs used for cancer research – as well as SSEP – on the final two Space Shuttle flights.

Each FME tube is 6.7 inches long (170 mm), with an outer diameter of 0.5 inches (13 mm) and an inner diameter of 3/8-inches (9.5 mm).

Type 1 FME:

Total Sealed Volume: 10.00 ml (this is volume after the two barbed stoppers are inserted in each end of the tube)

Type 2 FME:

Total Sealed Volume = Volume 1 + Volume 2: 9.2 ml (this is volume after the two barbed stoppers are inserted in each end of the tube)

Note: compared to a Type 1 FME, introduction of one clamp in the Type 2 reduces total volume by 0.8 ml

Note: minimum volume for Volume 1 or Volume 2 (achieved when a clamp is placed as close to the end of the tube as possible): 1.2 ml

Type 3 FME:

Total Sealed Volume = Volume 1 + Volume 2 + Volume 3: 8.4 ml (this is volume after the two barbed stoppers are inserted in each end of the tube)

Note: compared to a Type 1 FME, introduction of two clamps in the Type 3 reduces total volume by 2 x 0.8 = 1.6 ml

Note: minimum volume for Volume 1 or Volume 3 (achieved when a clamp is placed as close to the end of the tube as possible): 1.2 ml

Note: minimum for Volume 2 (achieved when both clamps placed as close to one another as possible): 1.9 ml

6.2 Experiment Samples—Restrictions on the Fluids and Solids That You Can Use in Your Experiment

Each SSEP experiment selected for flight must pass a NASA Flight Safety Review. The review is conducted by NASA Toxicology at Johnson Space Center, and is meant to ensure that the fluids and solid materials to be used in the experiment—the Experiment Samples—pose no risk to the astronaut crew, ferry vehicles, or ISS. The level of risk depends on the toxicity of the experiment samples AND how well they are contained in the mini-lab. The more “levels of containment” that are engineered into the mini-lab, the less the restrictions on the experiment samples. For each SSEP flight opportunity, NCESSE and Nanoracks work hard to ensure a high probability that each of the experiments passes Flight Safety Review. This is done by assessing the safety features engineered into the mini-lab to be used, and what restrictions this imposes on allowable experiment samples.

As a benchmark of success, all of the 421 SSEP experiments selected for flight on the first 20 SSEP flight opportunities (SSEP on the final flights of Shuttles Endeavour and Atlantis, and SSEP Missions 1 through 18 to ISS) passed Flight Safety Review. However, it is important to note that the final decision on whether an experiment passes the Review is NASA’s and out of the control of NCESSE and Nanoracks.

For SSEP Mission 19 to ISS, the FME Mini-lab has three nested and sealed enclosures surrounding the fluids and solids to guard against an accidental release into the crew cabin. This includes the main silicone tube, together with the two polyethylene bags Nanoracks will heat seal around the tube once the flight FME arrives in Houston (see Figure 5). The FME is said to have three levels of containment, and this provides so much redundancy against an accident that a very significant number of fluids and solids can be used by a student team. However, the following are restrictions and requirements regarding the fluids and solids that can be used in the FME Mini-lab:

a. Prohibited Samples: Student teams must NOT use any of the following fluids and solids.

radioactive fluids or solids

perfumes

hydrofluoric acid

magnets

cadmium

beryllium

acetone

technology (see details below)

Technology is prohibited for use in the FME Mini-lab and CANNOT be proposed by student teams. This includes batteries, lighting, and any device that is associated with electrical circuits and/or mechanical systems. Such technology is not covered by the NASA Flight Safety Review. It requires a more detailed and lengthy process of flight certification that does not fit within the timeline of SSEP Missions. SSEP therefore does not support flight certification of technology for placement inside the FME.

A finalist proposal submitted to NCESSE that makes use of any of the substances listed above will be rejected automatically and will not move forward to the Step 2 Review Board for review.

b. Hazardous Samples: Nanoracks and NASA can and will refuse other fluids/solids based on hazard level. All student teams proposing experiments are therefore advised to consider carefully the level of hazard posed by the samples they are planning to use, even if they are not included in the list of prohibited samples above. If your experiment is making use of something that is known to be hazardous, NCESSE advises you to alert us as soon as the potential hazard is identified as part of your experiment brainstorming. This approach will allow Nanoracks to assess the hazard and any potential impact on NASA Flight Safety Review before your team invests lots of time in experiment design and proposal writing.

Examples of hazardous samples that either cannot be used, or require NCESSE and Nanoracks review as soon as such a sample is being considered by a student team, include:

-fluids/solids that are hazardous enough that there is concern that the student team is even handling these substances

-fluids/solids that when mixed can result in excess heat and/or pressure inside the FME tube, leading to loss of containment; fluids/solids where there is evidence that excess heat – even chemically generated light – can adversely impact other FMEs that share the payload box on ISS

-biologicals with a designated BioSafety Level (BSL) of 2 or higher. Regarding a proposed BSL 2 biological, the student team will be required to have access to a BSL 2 certified laboratory and technicians for receipt and handling of the sample(s), and you may be required to follow additional safety precautions, including, but not limited to, taking on responsibility to correctly heat seal the double polyethylene containment bags (provided by Nanoracks) around the FME before shipping to Nanoracks in Houston, given Nanoracks may deem handling of the FME containing a BSL 2 biological too dangerous. There should be no expectation to fly a biological of BSL 3 or higher. See this CDC slideshow for information on BioSafety Level classifications.

-all chemical samples are subject to a NASA Toxic Hazard Classification. All chemicals are assessed by the NASA BioSafety Review Board on a case-by-case basis for every flight. Even though a chemical may not be hazardous on the ground it may be hazardous in space and could be classified in such a way that it cannot be flown in an FME. A chemical sample with a designated Toxicity Hazard Level 0 (THL 0) is deemed non-hazardous. A chemical sample designated THL 1 may require additional safety precautions (similar to those detailed above for biologicals), and protective gear for handling. A chemical sample designated THL 3 cannot be used.

c. Problematic Samples: There are a significant number of fluid/solid samples that can adversely interact with the FME’s tube assembly, including the silicone tube, nylon end caps, polycarbonate screw, Viton o-ring, and/or the heat-sealed polyethylene bags. These samples are on the Nanoracks List of Problematic Samples document downloadable at the Document Library. These materials cannot be used at 100% concentration, but may be used on a case-by-case basis depending on mixtures, concentrations, pH values, etc. Any fluids or solids being considered for use should be checked against the List of Problematic Samples. If any samples are on the list student teams are: 1) strongly advised to determine if any alternative (non-problematic samples) are available, and 2) advised to contact NCESSE immediately if it is determined that the problematic sample is essential to the experiment as proposed.

Important note: for a problematic sample, Nanoracks is likely to require the student team to conduct a Compatibility Test. If required, a Compatibility Test must be conducted in an actual FME Mini-lab, which means conducting the full experiment using the proposed volumes and concentrations of all fluid/solid samples, including the problematic sample, and run for the entire time the samples would be in the FME from loading through return to Earth, which can be assumed to be 6-8 weeks. If the sample is then found to have an adverse impact on the FME Mini-lab, the experiment will be immediately rejected, and not forwarded to Step 2 Review. Also note that it could potentially take weeks for Nanoracks, if needing to consult with NASA, to assess if a Compatibility Test is required. It is therefore highly unlikely there will be enough time to conduct a Compatibility Test before NCESSE selection of the community’s flight experiment, If a Compatibility Test is completed after an experiment has been selected as the flight experiment, and the results show incompatibility with the FME, the community’s flight slot will be forfeit. NCESSE therefore urges teams to find an alternative to any problematic sample.

d. Human Samples: All human samples, such as blood, will need to be tested for Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, HIV-1, HIV-2, HTLV-1, and HTLV-2. Before an experiment using human samples can be selected as a flight experiment, the team must provide to NCESSE a letter from the sample vendor, or a medical laboratory, stating that tests for the presence of these viruses in the sample can and will be conducted, and the sample will be free of the viruses listed above. This letter must accompany any finalist proposal submitted to NCESSE if the use of human samples is proposed. In addition, before a flight experiment will be accepted for flight, a letter of certification from the sample vendor, or a medical laboratory, must be received by NCESSE stating the sample has been tested and is free of the viruses listed above.

e. Ethical Use of Animals: The NASA Procedural Comments on the Care and Use of Animals (NPR 8910.1D) details guidelines for research pertaining to animals in experiments. Per section 4.5, titled Vertebrate Animals and Higher Order Cephalopods Section Review, use of vertebrate animals and higher order cephalopods requires extensive review and IUCAC approval, which is beyond the scope of the SSEP program. Therefore, no vertebrate animals or higher order cephalopod experiments will be allowed under SSEP. Vertebrate animals include all fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds. Higher order cephalopods include octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish.

f. Specificity of Samples: Before the selection of an experiment for flight can be confirmed, each flight experiment team must provide a list of their samples with the level of specificity described in the document Required Specificity for Description of Experiment Samples, which is available for download in the Document Library. Required information includes precise sample names, volumes, concentrations, and pH.

g. Required Safety Data Sheets (SDS) and Certificates of Control (CoC): Each student team is required to provide a standard Safety Data Sheet (SDS) for each of their experiment samples (fluids and/or solids). Each SDS must be dated within 5 years of the launch date, and must be from the vendor/manufacturer where you purchase the sample. For those samples where an SDS is not typically provided by the vendor, e.g., Tilapia fish eggs, NCESSE will provide the team the necessary guidance to submit the needed safety paperwork without undue burden. The SDSs need not be provided when the proposals are sent for review, but they must be made available for Flight Safety Review. Insert definition of a CoC and requirement.

An SDS must be: i) an SDS (Safety Data Sheet) and not the older version of the document the MSDS (Materials Safety Data Sheet); ii) from the same vendor from which you will secure the sample; and iii) dated within 5 years of the No Earlier Than (NET) launch date.

A CoC must be: i) from the same vendor from which you will secure the biological sample; ii) be obtained from a certified or reputable vendor; iii) include the vendor’s letterhead and/or logo, iv) include the species and/or strain of the biological (e.g., seed, micro-aquatic organism, bacteria, insect, etc.); and v) confirm that the biological was maintained in a controlled environment with no cross contamination with other species and/or strains, and in the case of seeds, confirmation that no pesticides were used.

Important notes about SDSs and CoCs:

– Easy ways to secure an SDS: assess if it is downloadable from the vendor’s website; contact the vendor; or search the Web (e.g., Googling the sample name + SDS + the vendor’s name). If for any reason you are unable to secure an SDS for a particular sample, please let us know. NCESSE will work with your team to identify how you can meet this Flight Safety Review requirement.

– Many vendors will have a standard CoC they are able to provide. Others will not have a standardized form and will require guidance. If for any reason you are unable to secure a CoC for a biological, please let us know. NCESSE will work with your team to identify how you can meet this Flight Safety Review requirement. For example, if you are flying seeds and a CoC is not available, you can choose to sterilize the seeds using the Nanoracks Instructions for Seed Sterilization (see Section 6.5 below)

– If the biological sample proposed is a seed, and that seed is an organic variety, an Organic Certification can take the place of a CoC. An Organic Certification is usually available at the seed vendor’s website.

6.3 Constraints Due to the Flight Timeline for SSEP Mission 19 to ISS

Important constraints on the design of your experiment are associated with the timeline from turnover of your flight FME to Nanoracks in Houston, to when it arrives back in Houston after its flight in space. While the milestones listed below remain tentative until NASA sets precise launch and landing dates for the ferry vehicles to and from the ISS, the milestones make it possible for the student proposing teams to design their experiment with the mission timeline in mind.

The relevant critical milestones for the mission timeline for SSEP Mission 19 to ISS—

- Deadline for Nanoracks in Houston to receive your flight FME: Launch minus 2.5 weeks

- Handover of the SSEP Payload to NASA: Launch minus 1 week

- SSEP payload is placed aboard the ferry vehicle: Launch minus 2 days

- Target launch date for SSEP Payload to ISS: Current target: Late Spring 2025

- Payload transferred to ISS: Launch plus approximately 2-3 days

- Payload transferred from ISS to ferry vehicle; spacecraft undocking and landing: Aim is for Launch plus approximately 4-6 weeks

- Your FME is ready for pickup in Houston or for return shipping to your community: Landing +(24-72) hours

These dates lead to the following conclusions:

a. it will take about 3 weeks from the time your flight FME is received by Nanoracks in Houston to the time it arrives at ISS

b. it will be on ISS for approximately 4 to 6 weeks before being transferred to the return vehicle, and the vehicle undocks for return to Earth

c. it will be 24 to 60 hours from the time the ferry vehicle undocks from ISS to when your FME returns to Earth and is ready for pick up in Houston or for return shipping to your community

d. it will be 7.5 to 8.5 weeks from the time your FME was originally received by Nanoracks in Houston to when your FME returns to Earth and is ready for pick up in Houston or for return shipping to your community

Also note that this timeline does not include the travel time for your experiment from your community to Houston, and from Houston back to your community.

These conclusions likely lead to the following constraints on your experiment design:

a. Your experiment likely needs to be in stasis (in a dormant or inactive state) until it arrives on ISS so that the experiment does not proceed in gravity for 3 or more weeks while awaiting launch. For example, if you are using biological samples, they need to be dormant until the experiment is initiated on ISS. Some examples of dormant biological samples include: seeds; dehydrated macroscopic organisms and eggs such as brine shrimp eggs; and hundreds of freeze-dried microscopic organisms like bacteria—all of which are commercially available. If the dormant biological sample is placed in one volume of the FME, the experiment can be initiated by an astronaut on ISS by unlatching the clamp and mixing the sample with a rehydration or nutrient fluid contained in the adjacent volume.

b. Dormant samples may benefit from refrigeration during transport of your flight FME from you to Houston and on to ISS. Nanoracks is arranging refrigeration for transportation of the FMEs from the moment your flight-ready FME arrives at Nanoracks to when it reaches the ISS (see Section 6.4 below).

Important note: refrigeration of FMEs aboard the ISS is not available.

c. Prior to the transfer of your FME to the ferry vehicle for return to Earth, you might want to terminate a biological experiment by introducing either a “fixative” which kills and preserves the biology, or by introducing a growth inhibitor which dramatically slows biological activity. This allows you to ‘shut-down’ the biology before it is returned to Earth and re-exposed to a gravity environment for up to 3 days before you receive it in Houston, or up to 5 days if FedEx overnight shipping is required from Houston to you. In addition, your flight team may not be ready for harvesting and analysis as soon as they receive the flight experiment, which is more reason to terminate the experiment before return to Earth. Terminating a biological experiment can be done in a Type 3 FME with a fixative or inhibitor in the third volume, where the appropriate clamp can be unlatched before the FME leaves ISS. For more information, read the document Using Biologicals in SSEP Experiments: Dormant Forms, Fixatives and Growth Inhibitors in the Document Library.

6.4 Temperature (Thermal) Control

There is no active temperature (thermal) control within the FME. You should therefore expect the FME to be subjected to whatever the temperature conditions might be along its route from handover of your FME to Nanoracks in Houston to return of your FME after its flight in space. So, as an example, if you ship via FedEx to Houston without any added thermal control, i.e., cold packs, depending on time of year, the FedEx truck can be exceedingly hot.

Provided for you below are the options and expectations for thermal control for different legs along the route.

SSEP is meant to offer real experiment opportunities on ISS that are interdisciplinary, and at the grade 5-16 level, intersect the science curriculum across the physical science, earth/space science, and biological science curricular strands. That said, SSEP experiments are exceptionally well suited to biology, as long as biological samples can be maintained in a relatively dormant state until reaching ISS. While many biologicals can be kept in a dormant state at room temperature, some of them require refrigeration at a temperature of 2-8ºC. We therefore work with Nanoracks to make refrigeration available for an FME over much of it’s journey, including the following legs (unless otherwise noted):

a. shipping of your FME from you to Nanoracks in Houston: you can ship with cold packs (there are real constraints provided by Nanoracks for how to do this successfully)

b. Nanoracks storage of your FME until handover to NASA: a student team can request their FME be refrigerated (at approximately 2-4ºC)

c. from Nanoracks handover to NASA, through loading aboard the ferry vehicle, launch, and transfer to ISS: a student team can request their FME be refrigerated (at approximately 2-4ºC)

d. aboard ISS, over the 4 to 6 weeks or more that your FME will be aboard ISS, there will be no refrigeration. During this time, you should expect the ambient conditions of the crew cabin, with a temperature of 21-24ºC (70-75°F) – a shirtsleeve environment.

e. from loading aboard the return ferry vehicle, to undocking, to landing, and transport to Houston (expected duration: 24-72 hours): no refrigeration is available for this leg

f. shipping from Nanoracks in Houston to you: you can request your package be shipped with the same cold packs used when you sent the FME to Houston

Additionally, teams requesting refrigeration during transportation to ISS, may want to have their experiment initiated shortly after arrival at ISS, given that the FMEs will be brought to room temperature on arrival, and remain at room temperature for the remainder of their stay aboard ISS.

Note that for Mission 19 to ISS, the thermal controls described above are the only ones available. For example, there will be no access to an incubator aboard ISS, nor can any of the samples be kept frozen during transportation or aboard ISS.

6.5 Sterilization

Sterilization of the FME Mini-lab: The student flight team needs to assess if sterilization of the FME is needed prior to filling, based on the nature of their experiment. If heat sterilizing an FME, do not exceed 390 deg F for the silicone tube, or 200 deg F for clamps and end caps. Heat sterilization is not recommended for tubes partially filled with samples given it may damage those samples, or cause expansion of samples already loaded and possibly lead to failure of the tube or clamp. Alternatively, sterilization can be done by gas (e.g. ETO), radiation, or chemicals. Nanoracks has made available protocols for sterilization of the FME. NCESSE will provide the Nanoracks document Sterilizing the Nanoracks MixStik [Fluid Mixing Enclosure (FME) Mini-Laboratory] and Components to Mission 19 communities. You are also free to Contact NCESSE at any time to receive this document.

Sterilization of the Experiment Samples (Fluids and Solids): It is particularly important for a student team flying a biological experiment to consider the need to sterilize not just the FME Mini-lab but also sterilize, or obtain in a sterilized form, the biological material and any other fluids and solids used. Without the use of sterilized fluids and solids, other unwanted biologicals will surely be present, such as microbes and fungi (e.g., yeasts and molds), and growth of these unwanted hitchhikers can easily cause failure of the experiment by killing the biologicals under study. This is one example of why it is vitally important for each student team to work with a professional researcher who is an expert in what is being studied. How each student team can identify an expert researcher advisor for their experiment, using Google Scholars Search, is covered in Section 3.3 on the To Teachers How to Move Forward page. In addition, regarding more specific experiment samples, Nanoracks has made available protocols for sterilization of seeds and of fruit and vegetable samples. NCESSE will provide the Nanoracks documents i) Nanoracks Instructions for Seed Sterilization and ii) Instructions for Produce Wash to Mission 19 communities. You are also free to Contact NCESSE at any time to receive this Document.

6.6 Lack of Light

All FME Mini-labs must be stowed in an opaque payload box, and there is no light source that can be placed in the payload box. Student teams must assume that their experiment will proceed in the dark. The only available light will be no more than 120 seconds on a given Crew Interaction Day, if the student team requests the Allowed Crew Interaction “Wait” with the modifier “expose to ambient light”. The FME will be removed from the payload box and exposed to the ambient light aboard ISS for 120 seconds, then returned to the payload box.

6.7 Other Important FME Constraints

The FME has no means of active data acquisition on orbit, and no provided power.